Sample text from Listening to a Continent Sing

Birdsong coast to coast, from seaside sparrows and laughing gulls on the Atlantic to wrentits and western gulls on the Pacific!

And all from the best seat imaginable, all from the seat of a bicycle, riding through an open-air amphitheater over nearly 5000 miles. We will linger and listen, marveling as pioneers, I tell myself, capitalizing on my decades of birdsong study to listen to this continent sing as no one has before.

- Virginia

Virginia, May 9, a Blue Ridge dawn.

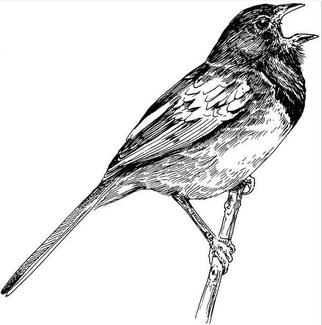

An hour before sunrise, the rain magically stops as we ease up the ramp to the Parkway just above Afton. White beacons of dogwood blooms line the way as we glide past whip-poor-wills jarring the night, when a roadside bush announces the day with a tentative chewink. A towhee, I smile. Others join in, with calling and fragmented singing, drink ... chewink ... teeeeeee ... your ... chewink ... drink teeeeee ..., successive calls and song bits all jumbled. In their dawn frenzy is no hint of the laid-back, repetitive singing they'll use later in the day.

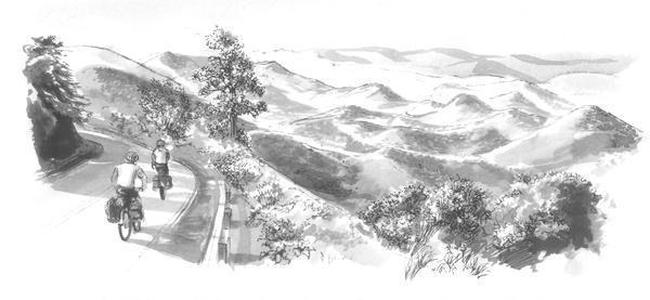

Whit-whit, wood thrushes awake, their two-voiced singing one of the wonders of eastern woodlands. And chip-burr, the call of a scarlet tanager from the canopy, followed by disjointed dawn song, the phrases delivered haltingly, punctuated every dozen or so by another chip-burr. For 40 minutes the wave of dawn light and song will pass, sweeping west to the Pacific, and we ride the wave, racing down the steep grades, slowing to a crawl on the uphills, all the while feasting on the dawn singing of ... chipping sparrows sputtering their songs from the ground ... lingering woodcocks skydancing overhead ... field sparrows chipping madly between complex songs three times the length of their normal daytime bouncing ball song ...

- Kentucky

Kentucky, May 16, Pippa Passes to Booneville.

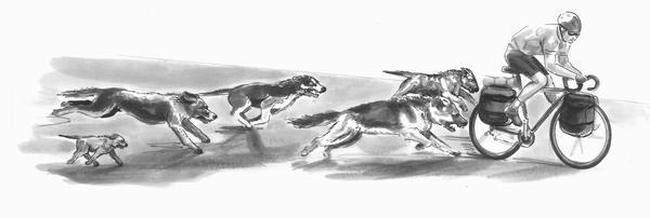

A little after 5 A.M., we ride through Alice Lloyd College on Purpose Road, crossing Integrity Lane, then Faith Avenue, then Action, Character, Conscience, Perseverance, Courage, Consecration. At each intersection, in the lighted bubble of a streetlight, are dawn-singing robins and phoebes and cardinals, each getting a jump on their singing day. Beyond the college, silence reigns, except for barking dogs, crowing roosters ... the you-allllllllll of a female barred owl.

All around us warblers announce the dawn: blue-wings stutter a tsi tsi tsi tsi tsi tis tsi zweeeeeeeeeeee ti ti ti; black-and-whites squeeze out a few thin, rapid wese wese notes, then drop to lower notes before ending high; parulas swirl skyward with a complex buzzy song. Each yellow works through a dozen different "sweet" songs; redstarts bounce among two to four songs; hoodeds sing with the same clear quality of their one tawee tawee tawee TEE-o daytime song, but each song now feels more jumbled, and successive songs are always different. Each warbler in his own excited voice, each in his own way, but on one matter they all agree: All airtime between songs must be filled with emphatic chipping.

About sunrise I hear the mood shift. Blue-wings offer their lazy beee-bzzzzzzzzz daytime song, black-and-whites their deliberate weesee-weesee-weesee, parulas their simpler daytime song as well. Now each yellow, redstart, and hooded delivers only his one special song that he's saved for once the dawn wave has passed.

- Illinois

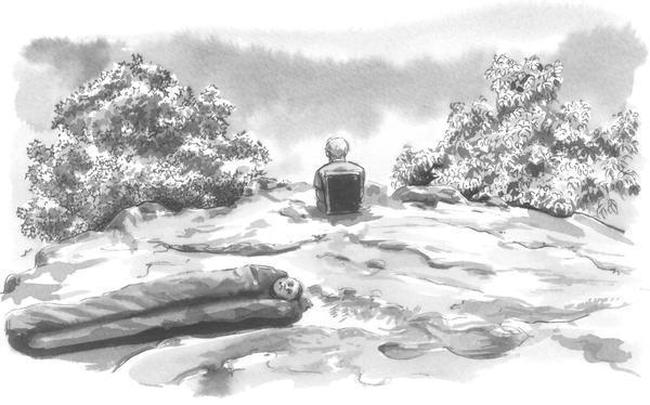

Illinois, May 27, Ferne Clyffe State Park.

An hour and a quarter before sunrise, I'm perched at the cliff's edge, comfortable in my camp chair, listening, smiling, breathing deeply, as if a deep breath might capture in my chest all that I feel and see and hear ... purple martins are high overhead, a small cloud of older males drifting about up there, perhaps luring late-migrating yearlings to the colony ... chuck-WILL'S-WID-ow, just below, loud and clear, a more faint WILL'S-WID heard from two others in the distance ... an indigo bunting bursts into song, as if unloading some nightmare, then is silent ... and a raucous outburst from a great crested flycatcher, then he too is silent ...

Just to my right awakes an Acadian flycatcher, a Mosquito Prince, an Empidonax: seet, seet, seet, seet, seet PEET-sah! seet, seet, seet PEET-sah! So energized, he calls repeatedly between the songs that he'll use in a less frenzied state throughout the day. Two phoebes, left and right--the pace escalates, each rapidly alternating his two songs, FEE-bee, FEE-b-bre-be, FEE-bee, FEE-b-bre-be, each in typical phoebe cadence, hustling to the FEE-b-bre-be, taking a micro-second breather before offering the next FEE-bee, the songs and their delivery all dictated by phoebe genes.

Pit-i-tuck. A summer tanager awakes, soon singing from the small oak just downslope. Like the scarlet, his dawn singing is also disjointed, the song phrases delivered deliberately but continuously, without pit-i-tuck punctuations.

As shadows give way to emerging colors in the landscape, the dawn singers yield to the day as well, and I listen to their changing voices, focusing on ... warblers, tanagers, buntings, flycatchers ... and nearly two hours after sunrise, I accept that the bicycle awaits, leaving my dawn perch for another day of listening on the road.

- Missouri

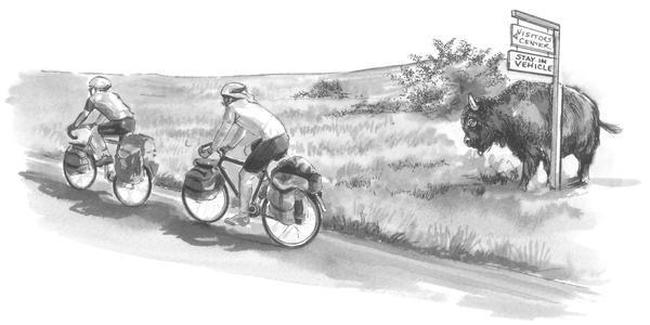

Missouri, June 2, Prairie State Park.

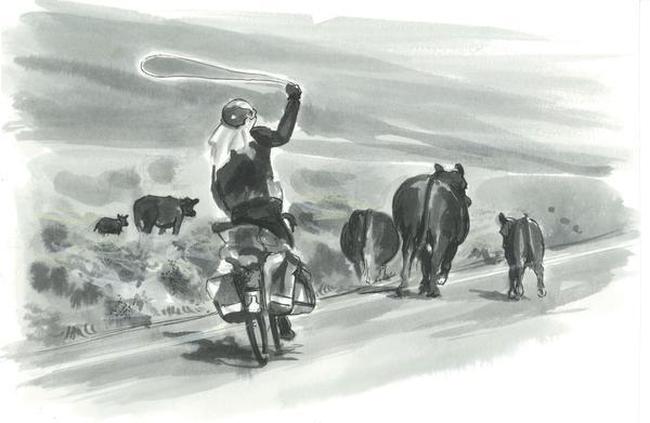

Yesterday, we bicycled down gravel NW 150th Lane into the heart of the Park; a vast blue sky welcomed us, extending to the horizon in all directions, with prairie flowers and songbirds and bison escorting us through pristine tallgrass prairie that had never seen a plow.

Come dawn, I'm out of the campground and into the prairie ... standing beside an isolated bush from which a Bell's vireo sings. I listen, recalling the few facts I know of his kind. Has maybe half a dozen different songs. Typically alternates two or three different songs, clearly heard by how distinctively some song endings rise and some fall. I listen for a recognizable song, knowing that it may occur 15-20 times among 50 or so songs over a few minutes, and then it will disappear, returning minutes later ... Yes, I hear all that. He's a "package singer," like chats and robins, like yellow-throated and blue-headed vireos, as he bundles certain of his songs together during his performance.

Dickcissels, each male perfectly in tune with the local dialect. Tup tup tup see-up sup sup, I hear, so different from the other dialect just down the road.

Cowbirds and meadowlarks and grasshopper sparrows and ... Henslow's sparrows! This is the Prairie, home of Prairie Birds! In a flight of fancy, I am a Henslow's sparrow, delivering my own unique tsi-lick song, beginning high, dipping and then climbing again, feinting, jogging, warbling briefly, pausing, resuming precipitously lower, on and on, each dip and jog and feint lasting no more than 1/100th of a second, the entire cascade of notes in my high-speed roller coaster song beginning near 10 kHz and ending at 3, lasting a glorious half second.

Back in the campground a special treat awaits: chickadees. On the hybrid zone here, the chickadees are all mixed up, most songs a combination of Carolina and black-cap traits.

- Kansas

Kansas, June 3-7.

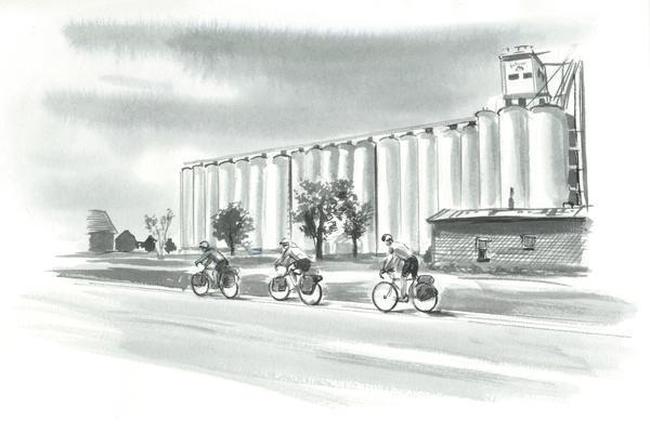

At 5 A.M., we roll out of the motel room to a Chanute that lies eerily asleep, to a ghost town of quiet streetlights standing sentinel, their nighttime shift nearing an end. About an hour before sunrise, robins rule the planet and airborne purple martins chortle as second in command. We head due west, on West 21st Street.

Nighthawks, everywhere their nearly continuous peents rain down on us, every ten or so interrupted by the loud VROOM of a dive display. Whoooooleeeee, wheeelooooo-ooooo--upland sandpipers, shorebirds without a shore; we ride on, entranced by these "Long Mellow Whistles," as ornithologists call them, every bit as memorable as the best cry of wolf or loon.

It's the land of little oil, ancient pumps littering the landscape and squeezing but a few barrels out of the ground each day. And of dickcissels. And of armadillos, in desperate need of advice from chickens on how to cross a road. And, surprisingly, of a few straggling eastern birds, with eastern phoebes at roadside bridges, eastern wood-pewees and great crested flycatchers in wooded stream bottoms.

At Harvey County East Park, dawn is a Tyrannus fest, where east and west meet south. Eastern kingbirds are first, four of them within earshot, each sputtering and stuttering sharply, t't'tzeer, t't'tzeer, T'TZEETZEETZEE, t't'tzeer, t't'tzeer, t't'tzeer, T'TZEETZEETZEE. From a small tree at the end of the campground I hear a kip kip kip ki-PIP ki-PEEP-PEEP-PEEP-PEEP--western kingbird.

And from a small locust next to the pavilion sings a scissor-tailed flycatcher! From beneath the pavilion, ever so slowly, I lean out to peek up beyond the roof overhang, and there he is, just two yards up! He perches facing me on a leafless, horizontal branch, his white chest glowing in the early light, his magnificent tail pumping noticeably with the exertion on each note. His stutter is low-pitched like that of the western kingbird, though sharper, and through the climax he becomes increasingly animated, ending on the loudest and highest note of all, surging at the end instead of fading like the western kingbird: pik pik pik pik pik pi-DIK PI-DIK PI-DAH PI-DAH-LEEK. The singing genes inherited from their kingbird ancestor dictate that males of all three species stutter and sputter before delivering their emphatic climax.

On the road, we magically float among the clouds, through patches of fog that hang over the fields and the road, the water-saturated air amplifying birdsong as if we ride through a great symphony hall. From small bushes beside the road rise the sharp, emphatic songs of Bell's vireos, accompanied by the wich-i-ty wich-i-ty of yellowthroats everywhere. A brown thrasher sings from a tree top to the right, pure and smooth, Kansas Kansas, so sweet so sweet, nice day nice day, ride on ride on, Oregon Oregon, the Pacific the Pacific ...

- Colorado

Colorado, Father's day, June 15, Kremmling.

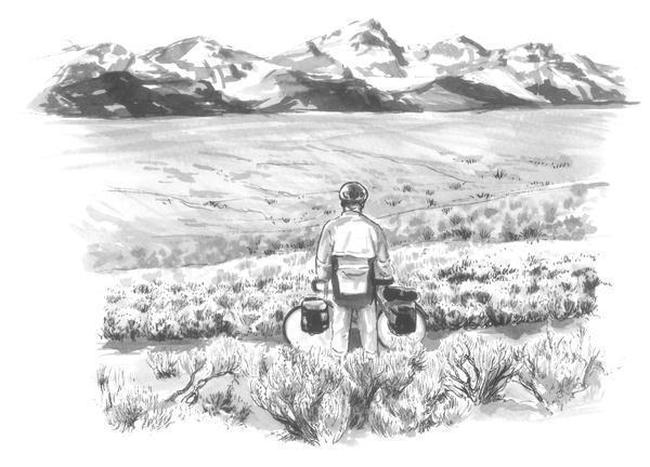

Awaking to my 4 A.M. alarm, I'm soon on the road. The orangish glow on the eastern horizon hints of the day to come, and the almost-full moon to the southwest hangs above the 2000-foot canyon carved there by the Colorado River. Outside town, the intense aroma of sage is intoxicating, as are the sounds of all that I hear: swallows singing on the wing, a mountain bluebird too; in what must be a wetland just off the road are yellow warblers, song sparrows, red-winged and yellow-headed blackbirds. Snipe winnow overhead.

I pedal on, slowly, savoring the now. The sage glows in the moonlight, and rising from the glow is a symphony of Brewer's sparrows and sage thrashers. The sparrow territories are small, with at least five birds always within earshot, all in wild dawn song. I pick out an individual beside the road as I slowly approach, hearing him work through high-pitched buzzes and trills and insect-like zeets, then cascade down to a long series of varied trills, then half a minute later rise again for another cycle. Their voices mix and mingle, and at any given instant some are near and loud, some far and soft, some high and some low, some clear and musical, others raspy and buzzy, their collective voices mesmerizing.

And the thrashers! What remarkable singers, but their territories are far larger, and I pass only one for every ten sparrows. Each races through his repertoire of hundreds of different sounds (about 700 in one bird I studied carefully), every half second (0.57 seconds to be exact, on average) hustling on to another sound at break-neck speed. And I hear their mimicry--how they love meadowlarks and Brewer's sparrows. He too is a package singer, favoring one set of songs for a time before moving on to others, though it takes hours (at least eight) rather than minutes for him to tell all he knows.

Vesper sparrows, rock wrens, western meadowlarks, magpies, nighthawks, horned larks ... and there, 5:10 A.M., 25 minutes before sunrise, the first Brewer's sparrow switches to his daytime song, a simple two-parted affair, zree zree zrrr-zrrr-zrrr, with no hint of the pre-dawn maestro. With two such different personalities, who would have known it's the same species.

I take the advice from a roadside savannah sparrow, take take take take-it eeeeeeeaaasssssssyyyyyyy. Ten seconds later, now well behind me, he repeats the wisdom in his lazy, high-pitched, almost insect-like song.

- Wyoming

Wyoming, June 19-20.

A few miles south of Dubois, we bicycle through a surreal wonderland of geologic history: The red, iron-rich sands and shales tell of warm climates during the Age of Reptiles, and the purple and black layers above them are from the Cretaceous, about 150 million years ago when birds were born!

At the entrance to the Tetons, for the better part of an hour we are overwhelmed by lightning and thunder and rain and wind. After the storm passes, we emerge from our aspen grove shelter and set out again, now in a calm, gentle rain, the sun shining magically through the parting thunderheads. Rounding the southern end of Jackson Lake, among the fir and spruce, we are buoyed by a symphony of Swainson's thrushes. The songs swirl and spiral upward, each breathy phrase higher and longer and louder than the one before, the entire performance as if lifting up so many spirits to the heavens. We bike from one singing male to the next, each of them seemingly singing "pass it on," until we break out into the open sage and grassland on our approach to Jenny Lake itself.

- Montana

Montana, June 28, Wisdom.

"3:00 A.M. 6-28"--so declares the lighted watch face when I punch my alarm off. With sunrise well over two hours away, I'm out the motel door, ready for yet another small bite out of our cross-country listening journey. At whatever speed I choose this morning, stopping where I please to look and listen, I will play my way across the sagebrush from here to the forest 11 miles away, and then ascend to Chief Joseph Pass, 25 miles to the west. My son and riding companion will follow later, and we'll meet up at the Pass.

With no moon, the constellations burn intensely against the still-black sky, the Milky Way an intense path through the heavens. The northern lights dance upward from the horizon, engulfing even the Great Bear. I listen, to the sound of darkness swishing past my ears, to the idea of dawn's first light and birdsong sweeping toward me from the east, to my own voice whispered into the night, "What a spectacular time of day to ride!"

A lone western marsh wren sings lazily off to the right, buzzing and rattling and whistling and trilling his way on an otherwise silent stage through more than a hundred different songs. A startled phantom flushes beside the road, kill-deer kill-deer kill-deer; overhead a dozen snipe winnow in earnest, wuwuwuwuwuwuwuwu, with the wind gusts from each wingbeat in their power dive whistling through their stiffened outer tail feathers. Seemingly thousands of tinkling bells announce horned larks in dawn song ... coyotes chorus off to the right ...

Just past the Big Hole National Battlefield lies the forest, with flycatchers in full dawn mode. Western wood-pewees, each rapidly alternating his two songs, tswee-tee-teet ... bzeeyeer ... tswee-tee-teet ... bzeeyeer ...; dusky flycatchers, pa-EET prrdurnt PIT-it, each with three different songs; willow flycatchers, too, FITZ-bew, FIZZ-bew, creet ... olive-sided flycatchers, just one song, hip! THREE CHEERS! ... I listen to each singer in turn, following along, marveling at how expressive he is.

And thrushes, what a gift to the ears this morning: Mountain bluebirds, robins, veeries, hermit and Swainson's thrushes, a varied thrush, and now a solitaire at the Pass.

- Idaho

Idaho, June 30.

West of the Lolo Pass divide between Montana and Idaho, drops and trickles and rivulets from the watershed here soon merge to form a roaring river that we swoop down to meet. A rainbow flies across the road in front of me, a male western tanager, the red and yellow and black and white aglow in the rays of the early morning sun shining over my shoulder. And a Steller's jay, shook shook shook he calls, flying so close I see the details, the black crest and head giving way to a sky blue belly, a grayish back, the deep, rich blue of the wings flashing with each stroke; in this light, he's radiant, iridescent even, the birds here as colorful as found in any lush rainforest, as if to remind us that we are no longer in the rain shadow of the Bitterroots.

In a flash we cover the ten miles to a stand of old-growth western red cedars that tower over the road. "THIS IS THE WEST," they shout, "the home of trees tall beyond measure, of cedars and redwoods and sequoias and Doug firs and more."

And the home of special birds. From somewhere deep in these cedars, a varied thrush sings. I have marveled at these songs on my computer, where I've played endlessly, slowing them down and speeding them up, listening to long sequences and trying to comprehend the overall effect. I follow along now, the first song high and buzzy; the next is lower pitched, more tonal; next he's high again; always, successive songs are different, the contrast striking. He plays with only four different songs, but each is actually two in one, because he sings two different songs simultaneously with his two voice boxes. "Try whistling and humming at the same time," I suggest to David, "and you get the effect." I listen on, smiling, the effect all the better knowing that Meriwether Lewis first heard and described these varied thrushes near here two hundred years ago.

- Oregon

Oregon, July 4-12.

A birthday present to myself, I again ride early, now out of Dayville by streetlight. On the right, from high in the trees near the post office, zip code 93825, a single wood-pewee alternates his two dawn songs. A deer spooks beside the road and crashes off through the brush. Just outside of town a western kingbird sputters through his dawn songs, and in the lush riparian habitat along the river I soon hear robins, song sparrows, yellow warblers, house wrens, house finches, lazuli buntings. To the left a California quail offers his chi-CAH-go, and high above a nighthawk calls.

As night eases into day, I have the world all to myself. It's just as Aldo Leopold wrote in his Sand County Almanac; the land deeds in the local courthouse mean nothing, because at this time of the morning the world belongs to me. With clear skies above and the temperature in the mid-50s, my bike rolls effortlessly down my valley along my John Day River. I am a rich man.

Through the geological chaos that is Oregon, among the remains of volcanic mountains scraped off ancient oceanic islands as the Pacific tectonic plate slid under North America, over the Cascade Range and into the Willamette Valley, over the Coast Range and on to the Pacific, I am all ears ... and saddened when I think of returning home to work at the University ... until I happily realize that I am no longer the professor I was just ten weeks ago ... I'm quitting the University, to celebrate life, full time, listening to birds ... and urging others to hear the wisdom in their voices, if only we would slow down and listen.